|

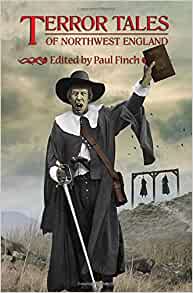

Top: R101 at her mast in Cardington Beds. Bottom: St Michael and All Angels Kesgrave Suff.

|

R101:

The Kesgrave Connection What could the giant sheds which brood over the landscape south of Bedford, a wooded hillside east of the French town of Beauvois and a Roman Catholic chapel in Kesgrave Suffolk possibly have in common? The answer, airship R101. Built with her sister ship, R100, in those selfsame hangers at RAF Cardington, and lost on her maiden flight when she crashed at Beauvois in the early hours of October 5th 1930. |

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Church of The Holy Family and St Michael was raised one year after the disaster as a memorial to her Assistant Chief Designer, Squadron Leader Michael Rope who perished with the airship. Born in Shrewsbury, Michael Rope graduated from Birmingham College as an engineer and, at the outbreak of the First World War, was drafted into the Royal Naval Air Service. In 1915, he became Lead Designer on the SS Zero airship project. The airship was highly successful and seventy-seven were eventually put into service in both reconnaissance and anti-submarine roles.

After the war, he transferred into the newly formed RAF and spent much of his early service in the Far East. It was while stationed at Martlesham Heath in Suffolk, however, that he met and fell in love with local girl Doreen Jolly from Grange Farm (in the days when it really was a farm) in Kesgrave.

Michael Rope (pictured) continued to work on airship design and construction, eventually joining the team responsible for producing the revolutionary new R101 at the Royal Airship Works based at Cardington. His contribution to the project was significant. Among his innovative developments were a "parachute" wiring system for securing the gas bags which gave the airship its lift, a new auto gas valve and a variable-pitch, wind-driven propeller to power the on-board electric generator. He became so intimately involved and dedicated to the new airship, his colleague T S D Collins was prompted to say of him that "he knew more about the R101 and about the mechanics of airship handling than anyone else in Britain."

The R101 itself was the flagship of British commercial aviation in that golden, pre-World War Two era of flying. The giant airships were seen as the future for long haul passenger and cargo flight. No aeroplane of the time could match them for payload capacity, endurance or comfort. The R101 and her sister, the R100, would, it was thought, open up the Empire, if not the world, for Britain.

From inception, the R101 was a revolutionary and ambitious project. Her shape alone, graceful, streamlined and aerodynamic was an immediate departure from the conventional cigar-shaped Zeppelin lines of previous airships. She was designed to carry a payload of sixty tons, including one hundred passengers in first class accommodation, on a return route between Britain and India. The hull, 731 feet long, was constructed from a framework of stainless steel girders covered by five acres of tightly stretched fabric. Inside were the giant gas bags filled with a five million cubic feet of highly-flammable but extremely light hydrogen.

There were two accommodation decks. The lower, contained the kitchen, control room, wireless room, crews quarters and access to the gondola - the airship's "bridge" - which was slung under her belly. The upper deck included passenger accommodation, a lounge, a promenade which ran past huge observation windows inserted into the hull fabric, a drawing room, a restaurant and even a smoking room, complete with armchairs, settees and asbestos-lined walls as a fire precaution!

However, from the very outset, the R101 was plagued by serious problems.

The hull fabric was susceptible to the rigours of the weather and was easily damaged. After one test flight, in relatively good conditions, a 140 foot rip was opened up along the airship's flank. This was repaired, but almost immediately another gaping hole appeared elsewhere in the hull. Another hazard was puncturing of the gas bags due to chafing against protruding structural steelwork inside the hull, especially when the airship flexed and twisted in bad weather, both reducing buoyancy and filling the hull with flammable hydrogen gas. The biggest problem, however, was lift. The first "lift and trim" test carried out in the giant Cardington shed revealed a lifting capacity of only 35 tons. The unfinished R101 was already 25 tons overweight.

Michael Rope's parachute wiring system was loosened to allow gas bag capacity to be increased. This created further chafing problems, cured as best as it could be by covering any protruding steelwork with fabric pads. Michael Rope was far from happy with this state of affairs and wrote to the Chief Designer, Lieutenant-Colonel Richmond expressing his concerns. They were, for the most part, ignored. Such was government pressure for a maiden flight to be accomplished that when an Air Ministry Inspector stated: "I cannot recommend the extension of the present permit to fly or the issue of any permit or certificate." his advice was totally disregarded and the Ministry simply wrote a flying permit out for themselves,

After a hastily arranged final test flight, carried out on October 1st - albeit in perfect weather and with the planned speed trials having to be abandoned through a combination of mechanical problems and lack of time - all was deemed to be ready for a maiden flight to Karachi.

Fifteen months earlier, at the height of construction, Michael Rope had married Doreen. Christopher Thomson, Secretary of State for Air and the driving force behind airship development, sent a telegram of congratulations. Lieutenant-Colonel Richmond commented that it was "almost bigamy" because Michael Rope was "married to the R101 already." When the R101, with 54 people - including the Air Minister himself - on board, slipped her moorings at the giant Cardington mast at 6:00 pm on Saturday October 4th 1930, Doreen Rope was expecting their first child.

After a circuit around Bedford, the airship headed south, passing over London on its way to the coast. Eyewitnesses speak of a huge, brightly-lit craft flying low overhead, of seeing passengers just visible through the glowing observation windows, and even of being able to hear dance music from the wireless installed in the airship's lounge.

The flight, however, quickly became a laboured struggle through worsening conditions. The airship, which had never been flown in bad weather or at maximum speed, rolled and pitched alarmingly. Holding her at a safe altitude of 1000 feet became increasingly difficult and there is evidence that she crossed the Channel at a dangerously low height.

At 2:00am on 5th October, while the passengers slept peacefully in their well-appointed cabins, the R101 passed over the French town of Beauvois. By now, hydrogen leakage from her incessantly chafing gas bags had reduced her buoyancy and she was flying well below safe altitude. Inhabitants of the town, awakened by the roar of her engines, saw the R101 pass low over their rooftops; storm-battered and rain-sodden. One of the duty crew reported finding a very tired Michael Rope patrolling the gantries within the hull, inspecting the rigging and gas bags, concerned, as ever, for the airship's safety.

Suddenly she slipped into a steep dive lasting a terrifying thirty seconds. Crockery and glass smashed. A crew member enjoying a quiet cigarette in the smoking lounge was thrown to the floor. Only swift action from the helm saved her from destruction, the airship's nose lifted for a moment. Then came the second, fatal dive. A poacher, Alfred Roubaille, out catching rabbits for his family's Sunday lunch, ran for his life as the titanic craft bounced across the wooded hillside east of Beauvois town. He saw the monster come to rest among broken trees, heard the hiss of escaping gas then the night was torn apart by a massive explosion.

Only eight of the souls on board managed to claw their way out of the nightmare inferno of burning fuel and hydrogen. Of these eight, two subsequently died of their terrible injures. The remaining forty-six people, including Christopher Thomson and Michael Rope perished in the wreck. Within minutes, all that was left of the great R101 was a twisted skeleton of scorched steel. Poignantly, her RAF ensign survived, hanging forlornly from the remains of her tail fin.

Word of the disaster reached RAF Martlesham Heath later that morning, via Kesgrave telephone exchange. The duty telephonist immediately contacted Doreen Rope's father William who broke the news to his daughter when she returned from church at lunch time.

In the months following the disaster, permission was given by Bishop Cary-Elwes for a chapel to be built in Kesgrave, on land donated by William Jolly, as a memorial to Michael Rope. The architects for the project were Messrs Brown and Burgess of Ipswich, who styled the new church on the traditional thirteenth century family chapel. The builders were W. C Reade of Aldeburgh. Work began in June 1931, with a private ceremony during which the foundation stone was laid on behalf of Michael Rope’s eight month old son Crispin.

Constructed of Suffolk brick with Weldon stone dressings, the original chapel seated sixty people. Many family members and friends contributed to the furnishing and decoration of the church. The stain glass window situated over the altar was donated by Michael Rope’s mother and depicts the Holy Family and Saint Michael to whom the church is dedicated. The R101 can be seen in the background. Mrs Rope also donated the chalice and monstrance. Four of the remaining windows were made by Michael’s sister Margaret who was a nun residing at a local Carmelite convent. Other nuns from the convent made the altar linen and vestments. The altar itself was constructed of unstained oak by Philip Jolly. A statue of Saint Michael stands in a niche above the porch and was made by Michael’s cousin Dorothy out of Stourbridge fire clay. Her sister Eileen contributed the panel above the nave door which shows Mary, the infant Jesus and St John the Baptist. The belfry, built some time after the chapel itself was completed, houses a ship’s bell, presented by Captain R Vaughn RN, husband of Michael Rope’s sister Irene. A scale model of the R101, made by the selfsame Cardington engineers who built the ill-fated original, hangs before the chancel arch. Some of the door fittings in the arch are made from metal salvaged from the airship wreck. An inscription under the Sanctuary window reads “Pray for Michael Rope, who gave his soul to God in the wreck of His Majesty’s Airship R101. Beauvois, October 5th, 1930.”

On December 7th 1931, the newly completed chapel was blessed by Canon Peacock of St Pancras, Ipswich. On the following day, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, it was opened as a “semi-public oratory”. Michael’s brother, Father H E G Rope, offered Mass and Canon Moriarty (later Bishop of Shrewsbury) preached to a congregation composed of members of the local clergy as well as relations and friends of those who died in the R101 disaster.

The Blessed Sacrament has been reserved ever since the opening of the Chapel and is safeguarded behind a set of wrought iron gates, built at Bredfield in Suffolk.

The chapel is served from St Mary’s in Ipswich and is now in regular use as a place of worship. The building was extended in 1955 to increase its seating capacity to 100. It was extended again in 1992. Temporarily closed for the work, it was reopened with a Mass on 5th October 1993, the sixty-third anniversary of the R101 crash.

And of Squadron Leader Michael Rope, who is buried at Cardington with his fellow R101 victims, this comment by one of his contemporaries makes a fitting epitaph: he was "an outstanding design genius but so modest and retiring that he tended to efface himself and to discount the credit which was his due. Few realised how gifted and valuable he really was."

First published in KESGRAVE NEWS 1994

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMAGES Clockwise from top left: Majestic and titanic R101 in flight | The airship sheds at Cardington Beds | The end of R101 | Inside St Michael and All Angels

The Church of The Holy Family and St Michael was raised one year after the disaster as a memorial to her Assistant Chief Designer, Squadron Leader Michael Rope who perished with the airship. Born in Shrewsbury, Michael Rope graduated from Birmingham College as an engineer and, at the outbreak of the First World War, was drafted into the Royal Naval Air Service. In 1915, he became Lead Designer on the SS Zero airship project. The airship was highly successful and seventy-seven were eventually put into service in both reconnaissance and anti-submarine roles.

After the war, he transferred into the newly formed RAF and spent much of his early service in the Far East. It was while stationed at Martlesham Heath in Suffolk, however, that he met and fell in love with local girl Doreen Jolly from Grange Farm (in the days when it really was a farm) in Kesgrave.

Michael Rope (pictured) continued to work on airship design and construction, eventually joining the team responsible for producing the revolutionary new R101 at the Royal Airship Works based at Cardington. His contribution to the project was significant. Among his innovative developments were a "parachute" wiring system for securing the gas bags which gave the airship its lift, a new auto gas valve and a variable-pitch, wind-driven propeller to power the on-board electric generator. He became so intimately involved and dedicated to the new airship, his colleague T S D Collins was prompted to say of him that "he knew more about the R101 and about the mechanics of airship handling than anyone else in Britain."

The R101 itself was the flagship of British commercial aviation in that golden, pre-World War Two era of flying. The giant airships were seen as the future for long haul passenger and cargo flight. No aeroplane of the time could match them for payload capacity, endurance or comfort. The R101 and her sister, the R100, would, it was thought, open up the Empire, if not the world, for Britain.

From inception, the R101 was a revolutionary and ambitious project. Her shape alone, graceful, streamlined and aerodynamic was an immediate departure from the conventional cigar-shaped Zeppelin lines of previous airships. She was designed to carry a payload of sixty tons, including one hundred passengers in first class accommodation, on a return route between Britain and India. The hull, 731 feet long, was constructed from a framework of stainless steel girders covered by five acres of tightly stretched fabric. Inside were the giant gas bags filled with a five million cubic feet of highly-flammable but extremely light hydrogen.

There were two accommodation decks. The lower, contained the kitchen, control room, wireless room, crews quarters and access to the gondola - the airship's "bridge" - which was slung under her belly. The upper deck included passenger accommodation, a lounge, a promenade which ran past huge observation windows inserted into the hull fabric, a drawing room, a restaurant and even a smoking room, complete with armchairs, settees and asbestos-lined walls as a fire precaution!

However, from the very outset, the R101 was plagued by serious problems.

The hull fabric was susceptible to the rigours of the weather and was easily damaged. After one test flight, in relatively good conditions, a 140 foot rip was opened up along the airship's flank. This was repaired, but almost immediately another gaping hole appeared elsewhere in the hull. Another hazard was puncturing of the gas bags due to chafing against protruding structural steelwork inside the hull, especially when the airship flexed and twisted in bad weather, both reducing buoyancy and filling the hull with flammable hydrogen gas. The biggest problem, however, was lift. The first "lift and trim" test carried out in the giant Cardington shed revealed a lifting capacity of only 35 tons. The unfinished R101 was already 25 tons overweight.

Michael Rope's parachute wiring system was loosened to allow gas bag capacity to be increased. This created further chafing problems, cured as best as it could be by covering any protruding steelwork with fabric pads. Michael Rope was far from happy with this state of affairs and wrote to the Chief Designer, Lieutenant-Colonel Richmond expressing his concerns. They were, for the most part, ignored. Such was government pressure for a maiden flight to be accomplished that when an Air Ministry Inspector stated: "I cannot recommend the extension of the present permit to fly or the issue of any permit or certificate." his advice was totally disregarded and the Ministry simply wrote a flying permit out for themselves,

After a hastily arranged final test flight, carried out on October 1st - albeit in perfect weather and with the planned speed trials having to be abandoned through a combination of mechanical problems and lack of time - all was deemed to be ready for a maiden flight to Karachi.

Fifteen months earlier, at the height of construction, Michael Rope had married Doreen. Christopher Thomson, Secretary of State for Air and the driving force behind airship development, sent a telegram of congratulations. Lieutenant-Colonel Richmond commented that it was "almost bigamy" because Michael Rope was "married to the R101 already." When the R101, with 54 people - including the Air Minister himself - on board, slipped her moorings at the giant Cardington mast at 6:00 pm on Saturday October 4th 1930, Doreen Rope was expecting their first child.

After a circuit around Bedford, the airship headed south, passing over London on its way to the coast. Eyewitnesses speak of a huge, brightly-lit craft flying low overhead, of seeing passengers just visible through the glowing observation windows, and even of being able to hear dance music from the wireless installed in the airship's lounge.

The flight, however, quickly became a laboured struggle through worsening conditions. The airship, which had never been flown in bad weather or at maximum speed, rolled and pitched alarmingly. Holding her at a safe altitude of 1000 feet became increasingly difficult and there is evidence that she crossed the Channel at a dangerously low height.

At 2:00am on 5th October, while the passengers slept peacefully in their well-appointed cabins, the R101 passed over the French town of Beauvois. By now, hydrogen leakage from her incessantly chafing gas bags had reduced her buoyancy and she was flying well below safe altitude. Inhabitants of the town, awakened by the roar of her engines, saw the R101 pass low over their rooftops; storm-battered and rain-sodden. One of the duty crew reported finding a very tired Michael Rope patrolling the gantries within the hull, inspecting the rigging and gas bags, concerned, as ever, for the airship's safety.

Suddenly she slipped into a steep dive lasting a terrifying thirty seconds. Crockery and glass smashed. A crew member enjoying a quiet cigarette in the smoking lounge was thrown to the floor. Only swift action from the helm saved her from destruction, the airship's nose lifted for a moment. Then came the second, fatal dive. A poacher, Alfred Roubaille, out catching rabbits for his family's Sunday lunch, ran for his life as the titanic craft bounced across the wooded hillside east of Beauvois town. He saw the monster come to rest among broken trees, heard the hiss of escaping gas then the night was torn apart by a massive explosion.

Only eight of the souls on board managed to claw their way out of the nightmare inferno of burning fuel and hydrogen. Of these eight, two subsequently died of their terrible injures. The remaining forty-six people, including Christopher Thomson and Michael Rope perished in the wreck. Within minutes, all that was left of the great R101 was a twisted skeleton of scorched steel. Poignantly, her RAF ensign survived, hanging forlornly from the remains of her tail fin.

Word of the disaster reached RAF Martlesham Heath later that morning, via Kesgrave telephone exchange. The duty telephonist immediately contacted Doreen Rope's father William who broke the news to his daughter when she returned from church at lunch time.

In the months following the disaster, permission was given by Bishop Cary-Elwes for a chapel to be built in Kesgrave, on land donated by William Jolly, as a memorial to Michael Rope. The architects for the project were Messrs Brown and Burgess of Ipswich, who styled the new church on the traditional thirteenth century family chapel. The builders were W. C Reade of Aldeburgh. Work began in June 1931, with a private ceremony during which the foundation stone was laid on behalf of Michael Rope’s eight month old son Crispin.

Constructed of Suffolk brick with Weldon stone dressings, the original chapel seated sixty people. Many family members and friends contributed to the furnishing and decoration of the church. The stain glass window situated over the altar was donated by Michael Rope’s mother and depicts the Holy Family and Saint Michael to whom the church is dedicated. The R101 can be seen in the background. Mrs Rope also donated the chalice and monstrance. Four of the remaining windows were made by Michael’s sister Margaret who was a nun residing at a local Carmelite convent. Other nuns from the convent made the altar linen and vestments. The altar itself was constructed of unstained oak by Philip Jolly. A statue of Saint Michael stands in a niche above the porch and was made by Michael’s cousin Dorothy out of Stourbridge fire clay. Her sister Eileen contributed the panel above the nave door which shows Mary, the infant Jesus and St John the Baptist. The belfry, built some time after the chapel itself was completed, houses a ship’s bell, presented by Captain R Vaughn RN, husband of Michael Rope’s sister Irene. A scale model of the R101, made by the selfsame Cardington engineers who built the ill-fated original, hangs before the chancel arch. Some of the door fittings in the arch are made from metal salvaged from the airship wreck. An inscription under the Sanctuary window reads “Pray for Michael Rope, who gave his soul to God in the wreck of His Majesty’s Airship R101. Beauvois, October 5th, 1930.”

On December 7th 1931, the newly completed chapel was blessed by Canon Peacock of St Pancras, Ipswich. On the following day, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, it was opened as a “semi-public oratory”. Michael’s brother, Father H E G Rope, offered Mass and Canon Moriarty (later Bishop of Shrewsbury) preached to a congregation composed of members of the local clergy as well as relations and friends of those who died in the R101 disaster.

The Blessed Sacrament has been reserved ever since the opening of the Chapel and is safeguarded behind a set of wrought iron gates, built at Bredfield in Suffolk.

The chapel is served from St Mary’s in Ipswich and is now in regular use as a place of worship. The building was extended in 1955 to increase its seating capacity to 100. It was extended again in 1992. Temporarily closed for the work, it was reopened with a Mass on 5th October 1993, the sixty-third anniversary of the R101 crash.

And of Squadron Leader Michael Rope, who is buried at Cardington with his fellow R101 victims, this comment by one of his contemporaries makes a fitting epitaph: he was "an outstanding design genius but so modest and retiring that he tended to efface himself and to discount the credit which was his due. Few realised how gifted and valuable he really was."

First published in KESGRAVE NEWS 1994

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMAGES Clockwise from top left: Majestic and titanic R101 in flight | The airship sheds at Cardington Beds | The end of R101 | Inside St Michael and All Angels